research report

investigating danish

modern design as an

allegory of a broader

cultural narrative

representing danish

societal values

investigating danish

modern design as an

allegory of a broader

cultural narrative

representing danish

societal values

Why the Danish

Do Design Better

Preface

While on vacation in Santa Fe, New Mexico during the summer of 2018, I visited a local mom-and-pop bookstore called “The Ark” that I had put on my to-do list. I was on a mission to buy a special 25th anniversary edition of Paulo Coehlo’s critically acclaimed novel The Alchemist, a book that I had never read before but remember wanting to while in middle school. Unfortunately, the book was always unavailable at both my school and local public libraries, either because it had been checked out or that they didn’t even carry a copy. This was also at a time when the Internet was in its infancy and the concept of e-commerce a novelty, thoroughly predating the age of Amazon and e-books. The Alchemist was therefore quite an elusive piece of literature.

Much like the book’s protagonist Santiago, my trek to The Ark felt like a pilgrimage to a foreign land (one dating back to antiquity, no less) in which I was to uncover some sort of hidden treasure. It also carried a sense of nostalgia and primitivism in that it brought me back to the days of yore when visiting brick-and-mortar bookstores, especially independent ones, was both customary and experiential.

Shortly after arriving at the bookstore, I unearthed what I had begun digging for at the age of 11. I left The Ark having purchased The Alchemist along with another book called The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing. Despite my excitement over having finally landed a copy of what was once a seemingly unattainable book in the former (granted, I probably could’ve bought one years ago had I been determined enough), I quickly found myself more interested in reading the latter.

In The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing, author and self-branded professional “cleaning consultant” Marie Kondo outlines her eponymous “KonMari Method” for creating an orderly personal living space. While the New York Times bestseller is ostensibly a how-to guide for tidying, I quickly realized that there was a more spiritual meaning beneath the surface level. Both the book and the physical act of removing clutter are allegories that touch on ideas of mental clarity, self-awareness, and personal well-being.

Kondo’s words inspired me to purge my belongings down to the core items that reflect what I value in the here and now. In so doing, I got reacquainted with desk space that I hadn’t seen in ages. This prompted me to finally discard a shabby desk chair that had been primarily used as a dumping ground for clothing hitherto. I decided that I wanted its replacement to be something not only comfortable to sit in, but also a statement piece of furniture. My determination to find a special chair resulted in the purchase of a vintage Børge Mogensen armchair in good condition [fig. 1], and eventually the discovery of another hidden treasure—Danish Modern.

Much like the book’s protagonist Santiago, my trek to The Ark felt like a pilgrimage to a foreign land (one dating back to antiquity, no less) in which I was to uncover some sort of hidden treasure. It also carried a sense of nostalgia and primitivism in that it brought me back to the days of yore when visiting brick-and-mortar bookstores, especially independent ones, was both customary and experiential.

Shortly after arriving at the bookstore, I unearthed what I had begun digging for at the age of 11. I left The Ark having purchased The Alchemist along with another book called The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing. Despite my excitement over having finally landed a copy of what was once a seemingly unattainable book in the former (granted, I probably could’ve bought one years ago had I been determined enough), I quickly found myself more interested in reading the latter.

In The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing, author and self-branded professional “cleaning consultant” Marie Kondo outlines her eponymous “KonMari Method” for creating an orderly personal living space. While the New York Times bestseller is ostensibly a how-to guide for tidying, I quickly realized that there was a more spiritual meaning beneath the surface level. Both the book and the physical act of removing clutter are allegories that touch on ideas of mental clarity, self-awareness, and personal well-being.

Kondo’s words inspired me to purge my belongings down to the core items that reflect what I value in the here and now. In so doing, I got reacquainted with desk space that I hadn’t seen in ages. This prompted me to finally discard a shabby desk chair that had been primarily used as a dumping ground for clothing hitherto. I decided that I wanted its replacement to be something not only comfortable to sit in, but also a statement piece of furniture. My determination to find a special chair resulted in the purchase of a vintage Børge Mogensen armchair in good condition [fig. 1], and eventually the discovery of another hidden treasure—Danish Modern.

fig. 1

Introduction

The Danish architect and industrial designer adheres to a philosophy whereby he or she has an obligation to create things with the earnest intention of enriching the lives of others. From its earliest origins in the 18th and 19th centuries, to its zeitgeist and commercial zenith during the mid-20th century, to its enduring legacy and contemporary appeal, Danish Modern design has always been rooted in this humanitarian ethos. As such, “Danish Modern” can be thought of as a social paradigm as much as an artistic vernacular—both of which are inextricably linked and symbiotically emblematic of a much broader and uniquely Danish cultural narrative predicated on utopian themes of altruism, egalitarianism, and hedonism.

Danish Modern, very fittingly so, was borne out of a series of populist movements beginning with Lutheran pastor and poet Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundvig (1783-1872), who in 1833-34 published his thoughts in favor of universal adult education—particularly that of tenant farmers. His rationale was such that he “wanted [ordinary] people to consider themselves a part of something bigger and to become confident and industrious citizens.” (Oda, 8-9) This eventually led to the founding of the Folk High School ten years later (although education was neither free nor compulsory). Separate social movements subsequently followed with the establishment of the Danish Women’s Citizens Association in 1871 and a Farmers’ Cooperative Association in 1880. Although unrelated to the Folk High School, both organizations were guided by a shared belief in equal human rights and social mobility.

A clear emphasis on craftsmanship with respect to furniture design was in existence well before those three social movements, dating as far back as 1770 when the Danish Royal Academy of Fine Arts began conducting written examinations of its students—testing their knowledge of drafting principles and eye for aesthetics.¹ Passage of this exam was necessary for a design license and (eventually) even an apprenticeship under a master craftsman. Thus formal expectations and high standards for skill have been institutional in Denmark for nearly 250 years.

The genesis of Danish Modern as currently conceived occurred in the 1920s after the founding of the German Bauhaus. From the onset, the Danish architects and industrial designers developed a distinct brand of functionalism in relation to the “particular concerns and needs of Danish society.” (12) Within this Danish school of functionalism were several unrelated institutional branches, the most notable one being led by architect and designer Kaare Klint.

In 1924, Klint established the Department of Furniture Design in the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. The academic curriculum was based on Klint’s personal design philosophy of customized scale. A professor himself, Klint had his students study the proportional relationships between chairs and the human body. In so doing, students learned how to tailor the dimensions of their furniture designs to human scale.

In 1927, the Furniture Industry Association began an annual exhibition showcasing the collaborative work of young designers and skilled craftsmen. It’s here that Danish Modern made its name and blossomed into a commercial industry, for the strong emphasis on collaboration gave birth to a movement in which “superior handcrafted furniture was created for the general consumer rather than for a rich elite”—a movement that stressed community, quality, and accessibility. (14) By the 1930s, the exhibition had become a venue in which the most talented furniture designers and workshops displayed their signature work, many of whom went on to become the most recognized leaders of Danish Modern.

¹ Standards of beauty were initially based on neoclassical styles of furniture from other European countries, namely France and England. Craftsmanship was therefore defined by one’s ability to recreate those styles.

Danish Modern, very fittingly so, was borne out of a series of populist movements beginning with Lutheran pastor and poet Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundvig (1783-1872), who in 1833-34 published his thoughts in favor of universal adult education—particularly that of tenant farmers. His rationale was such that he “wanted [ordinary] people to consider themselves a part of something bigger and to become confident and industrious citizens.” (Oda, 8-9) This eventually led to the founding of the Folk High School ten years later (although education was neither free nor compulsory). Separate social movements subsequently followed with the establishment of the Danish Women’s Citizens Association in 1871 and a Farmers’ Cooperative Association in 1880. Although unrelated to the Folk High School, both organizations were guided by a shared belief in equal human rights and social mobility.

A clear emphasis on craftsmanship with respect to furniture design was in existence well before those three social movements, dating as far back as 1770 when the Danish Royal Academy of Fine Arts began conducting written examinations of its students—testing their knowledge of drafting principles and eye for aesthetics.¹ Passage of this exam was necessary for a design license and (eventually) even an apprenticeship under a master craftsman. Thus formal expectations and high standards for skill have been institutional in Denmark for nearly 250 years.

The genesis of Danish Modern as currently conceived occurred in the 1920s after the founding of the German Bauhaus. From the onset, the Danish architects and industrial designers developed a distinct brand of functionalism in relation to the “particular concerns and needs of Danish society.” (12) Within this Danish school of functionalism were several unrelated institutional branches, the most notable one being led by architect and designer Kaare Klint.

In 1924, Klint established the Department of Furniture Design in the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. The academic curriculum was based on Klint’s personal design philosophy of customized scale. A professor himself, Klint had his students study the proportional relationships between chairs and the human body. In so doing, students learned how to tailor the dimensions of their furniture designs to human scale.

In 1927, the Furniture Industry Association began an annual exhibition showcasing the collaborative work of young designers and skilled craftsmen. It’s here that Danish Modern made its name and blossomed into a commercial industry, for the strong emphasis on collaboration gave birth to a movement in which “superior handcrafted furniture was created for the general consumer rather than for a rich elite”—a movement that stressed community, quality, and accessibility. (14) By the 1930s, the exhibition had become a venue in which the most talented furniture designers and workshops displayed their signature work, many of whom went on to become the most recognized leaders of Danish Modern.

¹ Standards of beauty were initially based on neoclassical styles of furniture from other European countries, namely France and England. Craftsmanship was therefore defined by one’s ability to recreate those styles.

Deconstructing Danish Modern

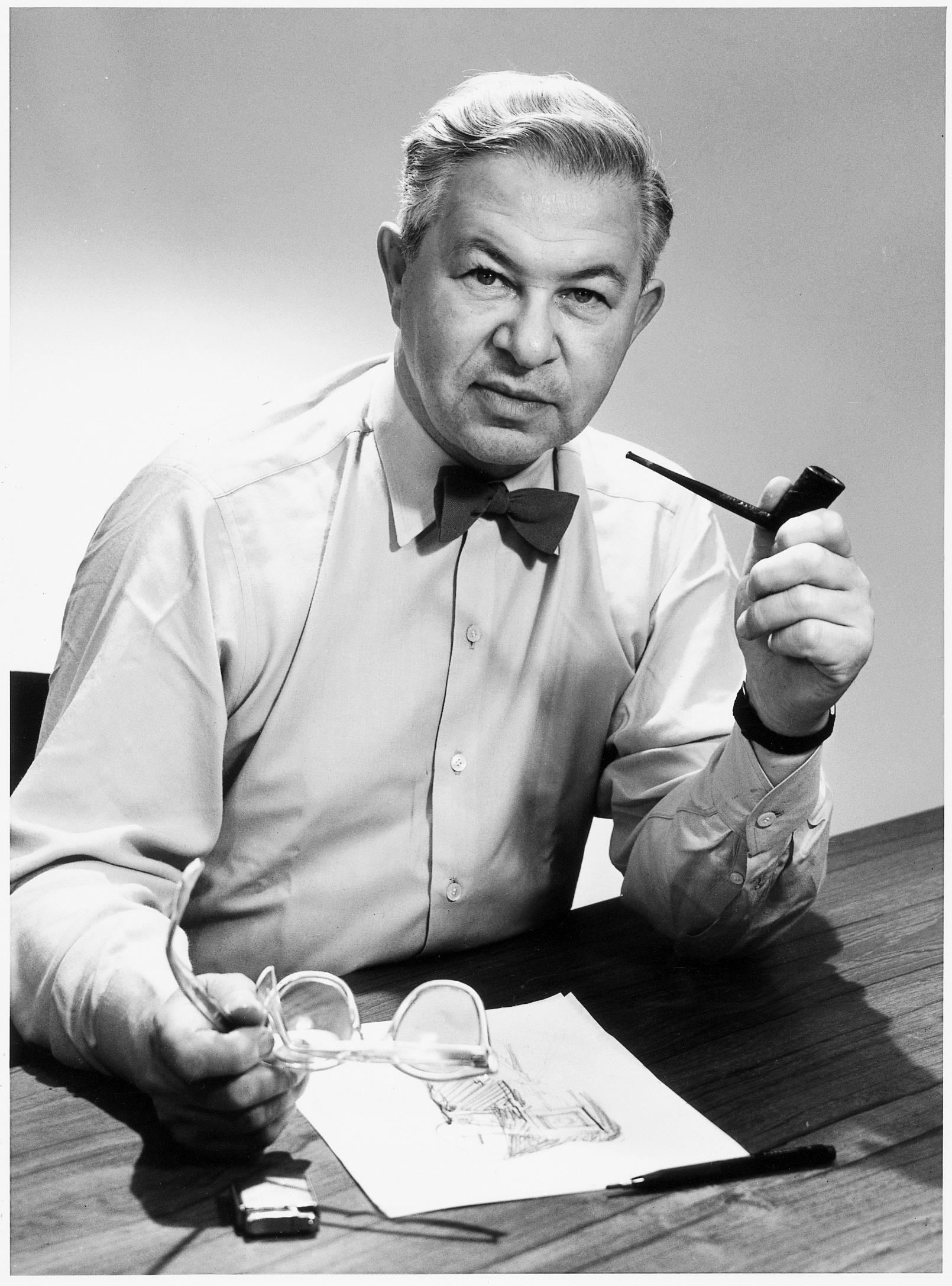

Quintessential Danish Modern furniture is firmly rooted in the craftsman tradition from which it evolved. As such, strong emphasis is placed on skill (by hand and machine, alike) being exercised by both designer and maker. This requires a rational understanding of materiality and its properties with respect to meeting human needs. To that end, the most frequently used material among furniture is wood (traditionally teak). Hans J. Wegner (1914- 2017) [fig. 2], the most prolific furniture designer of the Danish Modern movement, said the following:

The choice of wood stresses a reverence for the natural environment as well as durability. “Furniture was built to last because we couldn’t afford to go and buy another piece next year, and that idea is firmly planted in the heads of our designers,” according to Christian Rasmussen, the head of design at manufacturer Fritz Hansen. (Watson-Smyth) Lastingness also generates a keen sense of warmth and intimacy associated with handicraft. This regard for practicality and user experience is the cornerstone of Danish Modern as a whole; conception must be logical and configuration efficient.

While substance always takes precedent over style in terms of values, function and form can bear equal weight as far as splendor. The latter is often curvilinear in silhouette and simple in color palette, making the furniture ever more lasting in appeal and function. It’s precisely this symbiosis that constitutes, according to Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, a “special Danish mentality of combined common sense and a refined but unconstrained aesthetic sensibility.” (Kjeldsen, 11)

Although it undoubtedly shares philosophical, technical, and formal characteristics with similar design concepts that could also be classified under vague categorizations such as “Scandinavian,” “Nordic,” and “mid-century modern,” Danish Modern exists on its own merits. In other words, it’s not merely the nominally “Danish” version of something else that’s more or less the same.

Pallasmaa believes that there isn’t another country in which a “sense of continuous tradition and contemporariness, crafts and architecture, intellectualism and pragmatism, and a responsible social attitude and professionalism would have interacted as fruitfully as has been the case in Denmark.” (11) His insight is particularly cogent for the simple fact that he hails from Finland, which is a Nordic country within close proximity of what is considered to be traditional Scandinavia (Denmark, Sweden, Norway).²

Being Finnish affords Pallasmaa knowledge of the general commonalities among all Nordic cultures. It also allows him to be more perceptive to the cultural nuances between his Scandinavian neighbors as an outside observer. His observations, as clearly stated, express a belief that what we have come to regard as “Danish Modern” was the byproduct of specific cultural forces coalescing—a phenomenon that ultimately favored Denmark more than anywhere else (and to a disproportionate degree, no less). This is quite telling especially because the other Nordic nations share many of those core values and ideologies, yet none of them spawned their own equivalent to Danish Modern.

² Although Finland is a Nordic country, it’s not viewed as Scandinavian in a colloquial sense. This is largely due to palpable linguistic differences, as Finnish belongs to an entirely separate family than the other main Nordic languages—Danish, Swedish, Norwegian—all three of which are Indo-European and specifically part of the North Germanic subdivision of the Germanic branch.

“We dreamed of being able to make furniture as plain and natural as [possible]. Our material was wood, and in the mid-1940s there were still a number of good craftsmen left; we found it natural to use their knowledge and competence to help us build the new things we wanted to create.” (Øllgaard, 151)

The choice of wood stresses a reverence for the natural environment as well as durability. “Furniture was built to last because we couldn’t afford to go and buy another piece next year, and that idea is firmly planted in the heads of our designers,” according to Christian Rasmussen, the head of design at manufacturer Fritz Hansen. (Watson-Smyth) Lastingness also generates a keen sense of warmth and intimacy associated with handicraft. This regard for practicality and user experience is the cornerstone of Danish Modern as a whole; conception must be logical and configuration efficient.

While substance always takes precedent over style in terms of values, function and form can bear equal weight as far as splendor. The latter is often curvilinear in silhouette and simple in color palette, making the furniture ever more lasting in appeal and function. It’s precisely this symbiosis that constitutes, according to Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, a “special Danish mentality of combined common sense and a refined but unconstrained aesthetic sensibility.” (Kjeldsen, 11)

Although it undoubtedly shares philosophical, technical, and formal characteristics with similar design concepts that could also be classified under vague categorizations such as “Scandinavian,” “Nordic,” and “mid-century modern,” Danish Modern exists on its own merits. In other words, it’s not merely the nominally “Danish” version of something else that’s more or less the same.

Pallasmaa believes that there isn’t another country in which a “sense of continuous tradition and contemporariness, crafts and architecture, intellectualism and pragmatism, and a responsible social attitude and professionalism would have interacted as fruitfully as has been the case in Denmark.” (11) His insight is particularly cogent for the simple fact that he hails from Finland, which is a Nordic country within close proximity of what is considered to be traditional Scandinavia (Denmark, Sweden, Norway).²

Being Finnish affords Pallasmaa knowledge of the general commonalities among all Nordic cultures. It also allows him to be more perceptive to the cultural nuances between his Scandinavian neighbors as an outside observer. His observations, as clearly stated, express a belief that what we have come to regard as “Danish Modern” was the byproduct of specific cultural forces coalescing—a phenomenon that ultimately favored Denmark more than anywhere else (and to a disproportionate degree, no less). This is quite telling especially because the other Nordic nations share many of those core values and ideologies, yet none of them spawned their own equivalent to Danish Modern.

² Although Finland is a Nordic country, it’s not viewed as Scandinavian in a colloquial sense. This is largely due to palpable linguistic differences, as Finnish belongs to an entirely separate family than the other main Nordic languages—Danish, Swedish, Norwegian—all three of which are Indo-European and specifically part of the North Germanic subdivision of the Germanic branch.

fig. 2 / vitra design museum

The Dane as Craftsman

“Behind all Danish art lies the recognition that art is identical with skill,” proclaimed Viggo Kampmann, the Prime Minister of Denmark from 1960 to 1962. (Raoul, 119) Perhaps nobody was more attuned to this mindset than architect and industrial designer Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971) [fig. 3], the vanguard of Danish Modern.

Jacobsen’s artistry was one of daring vision and penchant for detail, his craft in alignment with the German concept of gesamtkunstwerk—the idea of art as a utopian system whose principles could be manifested in any conceivable form. As such, his oeuvre consists of everything from buildings to furniture to cutlery; it even includes ashtrays, a gas station, and a hot dog stand.

Nothing was too grand or minute for Jacobsen’s imagination; he simply wanted to design it all and make objects, activities, and experiences just a little bit better for everyone else. The totality of his work, though extensive and assorted, is the result of a singular reductionist approach that weds technical precision and ingenuity with basic functionality and sharp aesthetics.

Jacobsen’s proclivity for reductionism (e.g. minimalism) is most manifest in his architecture, which could be considered austere in appearance. However, this is merely a façade—literally and figuratively. Behind these exteriors exist interior spaces that are inviting and hospitable in atmosphere. “Outside a building might be brick or marble, but inside the interiors [are] always warm and nice. The colors [are often] in the dark blue to green range—the colors you observe in Danish nature,” according to Danish architect Regin Th. Schwaen. (Leslie, 42) On the Town Hall at Århus, one of Jacobsen’s more notable buildings, Schwaen adds: “Once inside, you just do not want to go home. A house like this is a house for the public.” (45)

Schwaen’s choice of the word “house” to describe a government building is a connotative reference to the central role Danish government plays in providing safety, Denmark often being identified as a “welfare state.” Furthermore, Schwaen adds a denotative qualifier by stating that the building exists for the people, thereby implying that the purpose of any Danish government is to serve its community. This underscores altruistic themes of inclusiveness and dependability—thoughtful, selfless qualities that are innate to Danish being.

Jacobsen’s design of the Town Hall is therefore an allegory of Danish Modern in every way possible; its marble-clad exterior [fig. 4] commands the respect of a governmental institution, while the interior space [fig. 5] exudes a sense of comfort and reassurance not often felt in bureaucratic environments. That Jacobsen was able to achieve this not only speaks to his immense skill as a designer, but also the way in which Danish government presents itself to the public and the vital relationship between the two. There’s a certain honesty and responsiveness to this rapport, and it’s only amplified and done justice by Jacobsen’s efficacy as an intermediate agent.

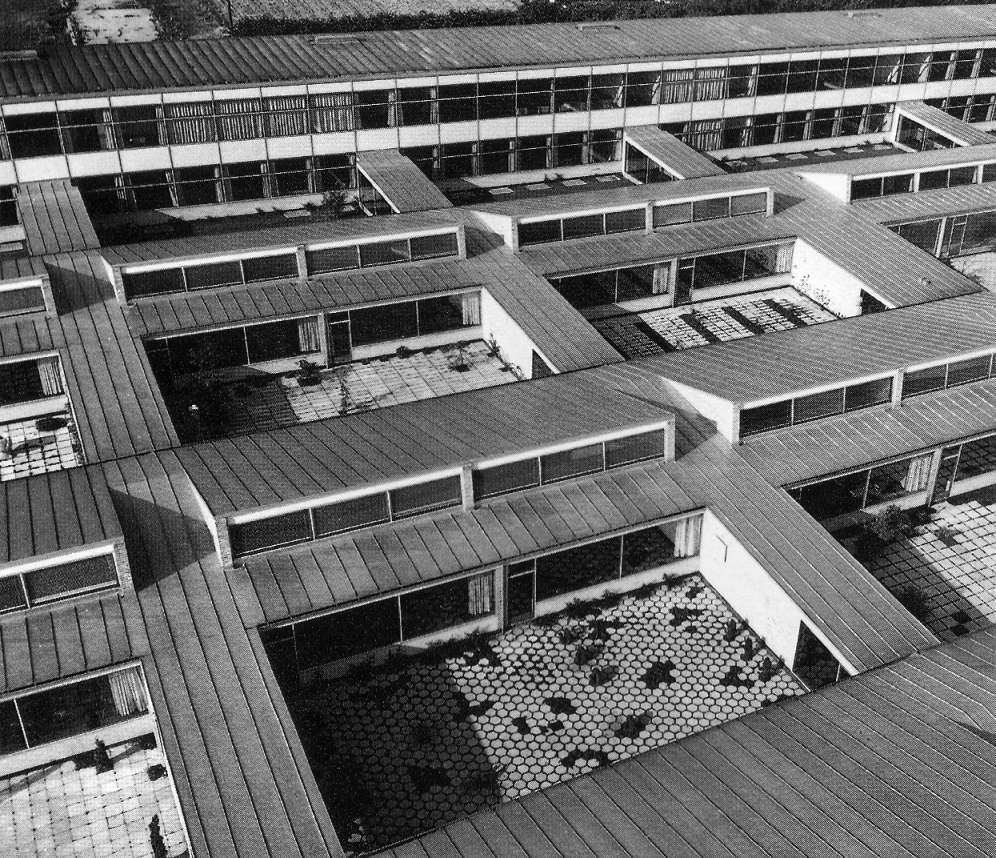

Notions of responsibility and responsiveness aren’t unique to the Town Hall, however. In designing the Munkegård Elementary School [fig. 6-7] in the Copenhagen suburb of Vangede, Jacobsen purposefully scaled down the building’s proportions to be less overpowering because he was cognizant of the fact that he was designing it for children. The high degree of empathy and self-awareness exhibited by Jacobsen in this instance demonstrates an uncompromising desire to create a space that’s in accordance with its audience, almost in an avuncular manner.

Much like Jacobsen did with his buildings, Wegner used a tailored approach in designing his chairs. Unlike Jacobsen, however, Wegner openly expressed a regard for aesthetics. “A chair should be beautiful from all sides and should not have a backside,” he dogmatically asserted. (Goodhart)

Over the course of his career, Wegner produced some 500 chair models, of which more than 100 went into mass production. One such chair was the “Peacock” (1947) [fig. 8], so named by fellow Danish designer Finn Juhl because it features a high-arched back made of thin wooden cylinders redolent of a peacock’s plumage. The wooden cylinders are strategically flattened so as to accommodate the shoulder blades of the person sitting in the chair. This is an example of Wegner “turning function into a decorative element” and “illustrat[ing] his belief in construction reflecting purpose,” according to Danish Modern: Between Art and Design author Mark Mussari. (Mussari, 56)

The end result is less an artifact to be admired from the outside and more an experience to be participated from the inside—another metaphorical example of democratic values. Wegner never lost sight of why he was designing what he was designing, despite the latter involving much delicate intricacy.

Jacobsen’s artistry was one of daring vision and penchant for detail, his craft in alignment with the German concept of gesamtkunstwerk—the idea of art as a utopian system whose principles could be manifested in any conceivable form. As such, his oeuvre consists of everything from buildings to furniture to cutlery; it even includes ashtrays, a gas station, and a hot dog stand.

Nothing was too grand or minute for Jacobsen’s imagination; he simply wanted to design it all and make objects, activities, and experiences just a little bit better for everyone else. The totality of his work, though extensive and assorted, is the result of a singular reductionist approach that weds technical precision and ingenuity with basic functionality and sharp aesthetics.

Jacobsen’s proclivity for reductionism (e.g. minimalism) is most manifest in his architecture, which could be considered austere in appearance. However, this is merely a façade—literally and figuratively. Behind these exteriors exist interior spaces that are inviting and hospitable in atmosphere. “Outside a building might be brick or marble, but inside the interiors [are] always warm and nice. The colors [are often] in the dark blue to green range—the colors you observe in Danish nature,” according to Danish architect Regin Th. Schwaen. (Leslie, 42) On the Town Hall at Århus, one of Jacobsen’s more notable buildings, Schwaen adds: “Once inside, you just do not want to go home. A house like this is a house for the public.” (45)

Schwaen’s choice of the word “house” to describe a government building is a connotative reference to the central role Danish government plays in providing safety, Denmark often being identified as a “welfare state.” Furthermore, Schwaen adds a denotative qualifier by stating that the building exists for the people, thereby implying that the purpose of any Danish government is to serve its community. This underscores altruistic themes of inclusiveness and dependability—thoughtful, selfless qualities that are innate to Danish being.

Jacobsen’s design of the Town Hall is therefore an allegory of Danish Modern in every way possible; its marble-clad exterior [fig. 4] commands the respect of a governmental institution, while the interior space [fig. 5] exudes a sense of comfort and reassurance not often felt in bureaucratic environments. That Jacobsen was able to achieve this not only speaks to his immense skill as a designer, but also the way in which Danish government presents itself to the public and the vital relationship between the two. There’s a certain honesty and responsiveness to this rapport, and it’s only amplified and done justice by Jacobsen’s efficacy as an intermediate agent.

Notions of responsibility and responsiveness aren’t unique to the Town Hall, however. In designing the Munkegård Elementary School [fig. 6-7] in the Copenhagen suburb of Vangede, Jacobsen purposefully scaled down the building’s proportions to be less overpowering because he was cognizant of the fact that he was designing it for children. The high degree of empathy and self-awareness exhibited by Jacobsen in this instance demonstrates an uncompromising desire to create a space that’s in accordance with its audience, almost in an avuncular manner.

Much like Jacobsen did with his buildings, Wegner used a tailored approach in designing his chairs. Unlike Jacobsen, however, Wegner openly expressed a regard for aesthetics. “A chair should be beautiful from all sides and should not have a backside,” he dogmatically asserted. (Goodhart)

Over the course of his career, Wegner produced some 500 chair models, of which more than 100 went into mass production. One such chair was the “Peacock” (1947) [fig. 8], so named by fellow Danish designer Finn Juhl because it features a high-arched back made of thin wooden cylinders redolent of a peacock’s plumage. The wooden cylinders are strategically flattened so as to accommodate the shoulder blades of the person sitting in the chair. This is an example of Wegner “turning function into a decorative element” and “illustrat[ing] his belief in construction reflecting purpose,” according to Danish Modern: Between Art and Design author Mark Mussari. (Mussari, 56)

The end result is less an artifact to be admired from the outside and more an experience to be participated from the inside—another metaphorical example of democratic values. Wegner never lost sight of why he was designing what he was designing, despite the latter involving much delicate intricacy.

fig. 3 / trent heritage collection

fig. 4 / the academy of urbanism

fig. 5 / grand tour magazine

fig. 6 / at1patios.wordpress.com

fig. 7 / at1patios.wordpress.com

fig. 8 / 1stdibs.com

Danish Sense and

Sensibility

Sensibility

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City held an exhibition called the “Arts of Denmark: Viking to Modern” from October 1960 to January 1961. Despite the fact that it was strictly organized to increase exports of Danish furniture and handicrafts to the United States, that avarice needn’t be condemned. According to Wegner, the impetus for Danish Modern’s success was simply that “Denmark was lagging behind in industrial development.” (Øllgaard, 151) Therefore, an exhibition of Danish industrial design as part of a larger presentation of cultural heritage seems hardly presumptuous.

In fact, judiciousness was on full display in this highly publicized showing of thousands of years’ worth of Danish arts and crafts, which was designed by Juhl. This was made even more apparent by the fact that the exhibition was headlined by Denmark’s King Frederik IX and Queen Ingrid. The royal couple was photographed in Central Park [fig. 9] a few weeks prior to the exhibition’s opening amongst a group of children. As they all gathered around the Hans Christian Andersen statue, a child asked, “King, where is your crown?” (Raoul, 121) While it’s quite likely that the 7-year-old boy was actually being sincere, any sense of disappointment he may have felt in that moment said nothing about the warm impression left by Europe’s oldest monarchy.

Indeed, the king’s figurative lack of a crown prudently foreshadowed the Arts of Denmark. In an article for the institution’s Bulletin (December 1960), author Rosine Raoul writes of the exhibition’s strikingly “democratic” display, noting that “roughly half the showing, both in number of objects and the space they occupy, is devoted to useful creations made since 1900, many of which may be bought... by people of moderate means and no pretensions to connoisseurship in the fine arts.” (121) Juhl’s skillful curation did his country and craft justice, for the “clarity and the sense of intention that pervade The Arts of Denmark make it a literally shining example of the graceful practicality we have learned to associate with Danish modern,” continues Raoul. (124)

In reaction to the exhibition, The New York Times went even further by stating the following:

Nearly sixty years later, those words remain true as Danish tradition would only have it.

Judiciousness is undoubtedly the tone of Danish Modern. Granted, minimalism inherently necessitates such in that the designer must have an acute ability to determine what’s indispensable and what’s superfluous. In other words, it requires the power of intellect. Danish Modern’s brand of minimalism is certainly cerebral. But what makes it truly compelling is that it’s fully contextualized and purpose-driven, and neither self-conscious nor contrived. The Danish Modern approach is such that all design is informed by the designer’s culture, not what the designer wants. Danish Modern isn’t minimalist because it wants to be; it’s minimalist because “Danish-ness” is fundamentally minimalist. The concept of altruism is wholly antithetical to notions of narcissism, greed, and nonchalance. In terms of Danish Modern, this translates into avoiding excess in the name of maintaining practicality and clarity.

Jacobsen applied this ethos to his furniture designs, seeking to achieve ergonomic comfort, functionality through economical materiality. His “Ant” chair (1952) [fig. 10], for instance, is the very embodiment of this method. Light and stackable, it consists of only two structural components—a sleek, curvilinear plywood frame and a steel base consisting of three cylindrical legs. Not unlike like the Town Hall, the Ant chair is duplicitous in that despite the stiff-looking appearance, it’s purportedly quite comfortable to sit in. The Ant is one of Jacobsen’s most famous chairs (alongside the Egg, Swan, and Series 7) and has been in continuous production by Fritz Hansen since it was first introduced in the 1950s. However prolific and innovative he was as a designer, Jacobsen wasn’t one to demand recognition or praise for his talents. He scrupulously believed that an artist’s persona and ego should never supersede their work.

The Danish in general are allergic to conspicuousness, preferring to blend in rather than stand out amongst their peers. This humility is central to sensible disposition (design and otherwise), for the “Danes’ love affair with modesty means that bragging about your accomplishments and flashing your Rolex are not only frowned upon [but also] considered poor taste.” (Weiking) For this very reason, “class is a highly embarrassing, unsettling subject,” writes scholar Jeppe Trolle Linnet in a journal article titled Money Can’t Buy Me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space. (Linnet, 25) Linnet goes on to state that Danes are “loath to classify himself or herself as anything but middle class” and that the “‘I am in-between’ social imaginary is pervasive and is repeated at all social levels.” (25) Danish character, in every sense of the word, is defined by this lack of pomp and circumstance and refusal to put oneself before others—at least within their own community.

In fact, judiciousness was on full display in this highly publicized showing of thousands of years’ worth of Danish arts and crafts, which was designed by Juhl. This was made even more apparent by the fact that the exhibition was headlined by Denmark’s King Frederik IX and Queen Ingrid. The royal couple was photographed in Central Park [fig. 9] a few weeks prior to the exhibition’s opening amongst a group of children. As they all gathered around the Hans Christian Andersen statue, a child asked, “King, where is your crown?” (Raoul, 121) While it’s quite likely that the 7-year-old boy was actually being sincere, any sense of disappointment he may have felt in that moment said nothing about the warm impression left by Europe’s oldest monarchy.

Indeed, the king’s figurative lack of a crown prudently foreshadowed the Arts of Denmark. In an article for the institution’s Bulletin (December 1960), author Rosine Raoul writes of the exhibition’s strikingly “democratic” display, noting that “roughly half the showing, both in number of objects and the space they occupy, is devoted to useful creations made since 1900, many of which may be bought... by people of moderate means and no pretensions to connoisseurship in the fine arts.” (121) Juhl’s skillful curation did his country and craft justice, for the “clarity and the sense of intention that pervade The Arts of Denmark make it a literally shining example of the graceful practicality we have learned to associate with Danish modern,” continues Raoul. (124)

In reaction to the exhibition, The New York Times went even further by stating the following:

“What all this suggests is that the Danish temperament is liberal, progressive, and experimental... one of the most comprehensive and successful and certainly one of the best advertised [welfare states].” (Hansen, 310)

Nearly sixty years later, those words remain true as Danish tradition would only have it.

Judiciousness is undoubtedly the tone of Danish Modern. Granted, minimalism inherently necessitates such in that the designer must have an acute ability to determine what’s indispensable and what’s superfluous. In other words, it requires the power of intellect. Danish Modern’s brand of minimalism is certainly cerebral. But what makes it truly compelling is that it’s fully contextualized and purpose-driven, and neither self-conscious nor contrived. The Danish Modern approach is such that all design is informed by the designer’s culture, not what the designer wants. Danish Modern isn’t minimalist because it wants to be; it’s minimalist because “Danish-ness” is fundamentally minimalist. The concept of altruism is wholly antithetical to notions of narcissism, greed, and nonchalance. In terms of Danish Modern, this translates into avoiding excess in the name of maintaining practicality and clarity.

Jacobsen applied this ethos to his furniture designs, seeking to achieve ergonomic comfort, functionality through economical materiality. His “Ant” chair (1952) [fig. 10], for instance, is the very embodiment of this method. Light and stackable, it consists of only two structural components—a sleek, curvilinear plywood frame and a steel base consisting of three cylindrical legs. Not unlike like the Town Hall, the Ant chair is duplicitous in that despite the stiff-looking appearance, it’s purportedly quite comfortable to sit in. The Ant is one of Jacobsen’s most famous chairs (alongside the Egg, Swan, and Series 7) and has been in continuous production by Fritz Hansen since it was first introduced in the 1950s. However prolific and innovative he was as a designer, Jacobsen wasn’t one to demand recognition or praise for his talents. He scrupulously believed that an artist’s persona and ego should never supersede their work.

The Danish in general are allergic to conspicuousness, preferring to blend in rather than stand out amongst their peers. This humility is central to sensible disposition (design and otherwise), for the “Danes’ love affair with modesty means that bragging about your accomplishments and flashing your Rolex are not only frowned upon [but also] considered poor taste.” (Weiking) For this very reason, “class is a highly embarrassing, unsettling subject,” writes scholar Jeppe Trolle Linnet in a journal article titled Money Can’t Buy Me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space. (Linnet, 25) Linnet goes on to state that Danes are “loath to classify himself or herself as anything but middle class” and that the “‘I am in-between’ social imaginary is pervasive and is repeated at all social levels.” (25) Danish character, in every sense of the word, is defined by this lack of pomp and circumstance and refusal to put oneself before others—at least within their own community.

fig. 9

fig. 10 / vinterior.co

A Danish Identity

The birth, growth, and maturation of Danish Modern as a cultural and commercial entity involved a search for national identity concomitant with a desire to shield itself from the influences of its much larger, more dominant neighbor Germany and later the United States. As such, Danish Modern was also a protective mechanism deliberately concocted to preserve Denmark’s own view of its “Danish-ness.” It was very much a reaction-based scheme that nurtured and grew itself through a process of inward reflection and an unwavering determination to be self-sufficient, despite a small population and few natural resources.

A 2017 study published by Oxford University calls this phenomenon “self-exoticization,” describing it as “moral s[k]epticism towards commercialization as ephemeral fashion and a loss of traditional values.” (Munch, 50) With Danish Modern becoming such an international commercial success by the mid-20th century, greater emphasis was placed on Denmark as a “‘small, densely populated country,’ still driven more by needs than dreams and unspoiled by foreign impulses and international trends.” (61)

The inscape of Danish Modern is therefore partially dependent upon Denmark’s xenophobia and geographic isolation, it being a continental European but culturally Nordic nation adjacent to a global industrial powerhouse. This renders the success of Danish Modern all the more impressive, for it illustrates a collective sense of cultural self-awareness and self-efficacy shared among Danish citizenry. Denmark is a country of independent thinkers with equal minds; its population understands that their strength is most effectively actualized through the togetherness that they espouse. Their obstinate sense of unified oneness and sameness in turn gives Danish Modern its voice and purpose.

A 2017 study published by Oxford University calls this phenomenon “self-exoticization,” describing it as “moral s[k]epticism towards commercialization as ephemeral fashion and a loss of traditional values.” (Munch, 50) With Danish Modern becoming such an international commercial success by the mid-20th century, greater emphasis was placed on Denmark as a “‘small, densely populated country,’ still driven more by needs than dreams and unspoiled by foreign impulses and international trends.” (61)

The inscape of Danish Modern is therefore partially dependent upon Denmark’s xenophobia and geographic isolation, it being a continental European but culturally Nordic nation adjacent to a global industrial powerhouse. This renders the success of Danish Modern all the more impressive, for it illustrates a collective sense of cultural self-awareness and self-efficacy shared among Danish citizenry. Denmark is a country of independent thinkers with equal minds; its population understands that their strength is most effectively actualized through the togetherness that they espouse. Their obstinate sense of unified oneness and sameness in turn gives Danish Modern its voice and purpose.

The Danish Live Well

Denmark is frequently recognized as one of the “happiest” nations on Earth due to the same sociocultural values that inform Danish Modern. In their 2018 “Best Countries” rankings, U.S. News & World Report places Denmark third in the “Citizenship” category—a metric that equally weighs eight different attributes pertaining to social capital. These include a regard for human rights, the environment, gender equality, progressiveness, religious freedom, property rights, trustworthiness, and balance of political power. Although Scandinavian neighbor Norway ranks first overall (Switzerland second), it should be noted that the survey’s participants rank Denmark the highest country in terms of human rights and gender equality.³ This reaffirms the notion that Denmark, more than any other country, cares deeply about the welfare of its people.

Denmark ranks second (behind Canada) in the “Quality of Life” category, which also equally measures each of its nine attributes—affordability, job opportunity, economic stability, family friendliness, income equality, political stability, safety, public education, and public healthcare. In income equality, public education, and public healthcare—arguably the most egalitarian attributes—Denmark receives a perfect score.

A separate study conducted in 2009 called The Danish Effect: Beginning to Explain High Well-Being in Denmark concludes that those three attributes are the most vital in terms of procuring happiness, citing that “low income Danes appear to experience well-being on par with the high income Danes” as proof of egalitarianism to the highest degree, which they call the “Danish Effect.” (Biswas-diener, 243-44)

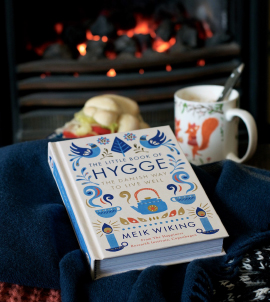

Well-being is the raison d’être of Danish Modern, representing ideas of comfortable living and living comfortably. Neither the former nor latter are exclusive to physical spaces or objects, however. Danish Modern also takes on spiritual meaning in the practice of hygge (pronounced “hoo-gah”). Meik Wiking, CEO of the Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen, literally wrote the book on hygge. In The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living [fig. 11], Weiking gives the following definition:

There isn’t a literal definition of the word, perhaps owing to the fact that its exact origins are unknown. According to Weiking, “hygge” might be derived from hygga (“to comfort” in Old Norse), which in turn is derivative of hugr (meaning “mood”). He also speculates that it could possibly originate from the word “hug,” which comes from hugge (“to embrace”). The etymology of “hugge” is unknown, although it may be from “hygga” itself. Nevertheless, those words all have connotative values of coziness, mindfulness, and togetherness. Hygge is about being mentally present and recognizing special moments while they’re happening in real time. Although it’s a sensation that can be experienced by anyone, anywhere, at any moment, ethnographer Stephen Borish writes that “[t]he ability to participate easily in social encounters that bring [hygge] to life is a part of the Danish heritage that others can well regard with envy.” In other words, nobody practices hygge more or better than the Danish do. (Linnet, 24)

Hygge is most often “achieved” in the setting of one’s own home for seven out of ten Danes. Interior design thus plays a prominent role in incubating hyggelige (“hygge-like”) conditions. The Danish firmly believe that good interior design promotes personal well-being, so much so that they created a nonprofit organization solely dedicated to that idea. Launched in 2002, “Index: Design to Improve Life” is now an internationally recognized competition that awards its winner the largest monetary prize for design.

While there aren’t formal design guidelines for achieving hygge, interiors are generally “clean and minimalist” in the form of “white walls and floorboards” set against “simple, utilitarian furniture.” (Watson-Smyth) The color palette is largely of the neutral and muted variety, perhaps accented with a pop of color from a singular source such as a lamp, cushion, or chair. The curtains are “white and open” to maximize natural light because of long, dark winters. (Watson-Smyth) Candles—and lots of them—are absolutely essential to hygge of the Danish flavor. [fig. 12] Rasmussen of Fritz Hansen states that “[p]eople spend a lot of time and energy on their homes because it is our way of showing who we are, how we live and what we believe in—and we believe absolutely that beautiful interiors make people happy.” (Watson-Smyth)

With such strong correlations between home, hygge, and interior design, it’s no surprise that the Danish have the distinct honor of enjoying the most living space per capita of any European country at 51 square meters per resident.⁴ This is in spite of the fact that Denmark has a relatively high population density due to its small geographic footprint, which undoubtedly contributes to ideas of coziness and solidarity.

³ The study surveyed over 21,000 people from 36 countries in four regions (the Americas, Asia, Europe and the Middle East, Africa) who were chosen because they were “broadly representative of the global population.”

⁴ The only other Scandinavian country that’s comparable to Denmark in this regard is Sweden, which is tied with the United Kingdom for second place at 44 square meters per resident.

Denmark ranks second (behind Canada) in the “Quality of Life” category, which also equally measures each of its nine attributes—affordability, job opportunity, economic stability, family friendliness, income equality, political stability, safety, public education, and public healthcare. In income equality, public education, and public healthcare—arguably the most egalitarian attributes—Denmark receives a perfect score.

A separate study conducted in 2009 called The Danish Effect: Beginning to Explain High Well-Being in Denmark concludes that those three attributes are the most vital in terms of procuring happiness, citing that “low income Danes appear to experience well-being on par with the high income Danes” as proof of egalitarianism to the highest degree, which they call the “Danish Effect.” (Biswas-diener, 243-44)

Well-being is the raison d’être of Danish Modern, representing ideas of comfortable living and living comfortably. Neither the former nor latter are exclusive to physical spaces or objects, however. Danish Modern also takes on spiritual meaning in the practice of hygge (pronounced “hoo-gah”). Meik Wiking, CEO of the Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen, literally wrote the book on hygge. In The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living [fig. 11], Weiking gives the following definition:

“Hygge is about an atmosphere and an experience, rather than about things. It is about being with the people we love. A feeling of home. A feeling that we are safe, that we are shielded from the world and allow ourselves to let our guard down. You may be having an endless conversation about the small or big things in life—or just be comfortable in each other’s silent company—or simply just be by yourself enjoying a cup of tea.” (vi)

There isn’t a literal definition of the word, perhaps owing to the fact that its exact origins are unknown. According to Weiking, “hygge” might be derived from hygga (“to comfort” in Old Norse), which in turn is derivative of hugr (meaning “mood”). He also speculates that it could possibly originate from the word “hug,” which comes from hugge (“to embrace”). The etymology of “hugge” is unknown, although it may be from “hygga” itself. Nevertheless, those words all have connotative values of coziness, mindfulness, and togetherness. Hygge is about being mentally present and recognizing special moments while they’re happening in real time. Although it’s a sensation that can be experienced by anyone, anywhere, at any moment, ethnographer Stephen Borish writes that “[t]he ability to participate easily in social encounters that bring [hygge] to life is a part of the Danish heritage that others can well regard with envy.” In other words, nobody practices hygge more or better than the Danish do. (Linnet, 24)

Hygge is most often “achieved” in the setting of one’s own home for seven out of ten Danes. Interior design thus plays a prominent role in incubating hyggelige (“hygge-like”) conditions. The Danish firmly believe that good interior design promotes personal well-being, so much so that they created a nonprofit organization solely dedicated to that idea. Launched in 2002, “Index: Design to Improve Life” is now an internationally recognized competition that awards its winner the largest monetary prize for design.

While there aren’t formal design guidelines for achieving hygge, interiors are generally “clean and minimalist” in the form of “white walls and floorboards” set against “simple, utilitarian furniture.” (Watson-Smyth) The color palette is largely of the neutral and muted variety, perhaps accented with a pop of color from a singular source such as a lamp, cushion, or chair. The curtains are “white and open” to maximize natural light because of long, dark winters. (Watson-Smyth) Candles—and lots of them—are absolutely essential to hygge of the Danish flavor. [fig. 12] Rasmussen of Fritz Hansen states that “[p]eople spend a lot of time and energy on their homes because it is our way of showing who we are, how we live and what we believe in—and we believe absolutely that beautiful interiors make people happy.” (Watson-Smyth)

With such strong correlations between home, hygge, and interior design, it’s no surprise that the Danish have the distinct honor of enjoying the most living space per capita of any European country at 51 square meters per resident.⁴ This is in spite of the fact that Denmark has a relatively high population density due to its small geographic footprint, which undoubtedly contributes to ideas of coziness and solidarity.

³ The study surveyed over 21,000 people from 36 countries in four regions (the Americas, Asia, Europe and the Middle East, Africa) who were chosen because they were “broadly representative of the global population.”

⁴ The only other Scandinavian country that’s comparable to Denmark in this regard is Sweden, which is tied with the United Kingdom for second place at 44 square meters per resident.

fig. 11 / lattelisa.blogspot.com

![]()

fig. 12 / 79ideas.org

fig. 12 / 79ideas.org

Conclusion

Danish Modern represents a uniquely Danish phenomena because it’s an evolutionary product of a series of cultural forces synchronously converging together. To be clear, none of those cultural forces (i.e. fine craftsmanship, minimalism, nationalism, and even hygge, to name a few) in isolation are exclusive to Denmark. Rather, it’s the interaction of those forces and their specific circumstances and nuances that laid a foundation bearing the most optimal conditions for birthing a movement like Danish Modern. Said conditions were heavily concentrated in Denmark, more so than any other country.

The nurture of Danish Modern was based on a clear and collectively shared sense of identity and purpose among Danes, architecture and industrial design being physical manifestations of that self-awareness. When Danish Modern became an internationally exported commercial success, the Danish naturally feared losing the very same traditions and values that gave rise to its viability in the first place. This trepidation was expressed in the form of self-reevaluation, the Danish eventually determining that they wanted to protect their cultural heritage by reasserting said traditions and values.

One might say that such preoccupation with national identity is an overt display of self-consciousness antithetical to Danish Modern’s moralistic philosophy. However, it must be re-emphasized that the Danes’ self-consciousness was based on an introspective process in keeping with their tradition. Their concerns surrounding loss of identity were founded on the same rationalist logic that informed Danish Modern design, which is a respect for cultural origins.

Denmark perennially finds itself at or near the top of lists regarding happiness and quality of life, which is clear evidence of a society as functional as the furniture it’s associated with. Danish Modern furniture, with its connotations of comfort and warmth, are tangible signifiers of the intangible sensation hygge. Hygge in turn represents the spiritual essence of Danish Modern as a cultural narrative defined by its humanitarian ethos—design and being becoming indiscernible co-authors.

Although its zeitgeist has long since passed, Danish Modern’s legacy (fittingly) remains undisturbed. For instance, Jacobsen’s most famous chairs have been in continuous production by the same manufacturer since they debuted in the 1950s, which is to say that they’re timeless pieces. In fact, Danish Modern design in general is often thought of as being “timeless.” While its well-conceived and well-constructed forms are certainly qualities that render it so, the driving force behind this timelessness is what the design represents. At its core, Danish Modern is based on intellect and a desire for improvement—two things that will never lose their cachet within civilization. Human rights, gender equality, socioeconomic disparity, and public infrastructure (namely education and healthcare) are all hot-button topics today, but not in Denmark. Danish Modern is timeless precisely because it was ahead of its time by about 150 years.

The nurture of Danish Modern was based on a clear and collectively shared sense of identity and purpose among Danes, architecture and industrial design being physical manifestations of that self-awareness. When Danish Modern became an internationally exported commercial success, the Danish naturally feared losing the very same traditions and values that gave rise to its viability in the first place. This trepidation was expressed in the form of self-reevaluation, the Danish eventually determining that they wanted to protect their cultural heritage by reasserting said traditions and values.

One might say that such preoccupation with national identity is an overt display of self-consciousness antithetical to Danish Modern’s moralistic philosophy. However, it must be re-emphasized that the Danes’ self-consciousness was based on an introspective process in keeping with their tradition. Their concerns surrounding loss of identity were founded on the same rationalist logic that informed Danish Modern design, which is a respect for cultural origins.

Denmark perennially finds itself at or near the top of lists regarding happiness and quality of life, which is clear evidence of a society as functional as the furniture it’s associated with. Danish Modern furniture, with its connotations of comfort and warmth, are tangible signifiers of the intangible sensation hygge. Hygge in turn represents the spiritual essence of Danish Modern as a cultural narrative defined by its humanitarian ethos—design and being becoming indiscernible co-authors.

Although its zeitgeist has long since passed, Danish Modern’s legacy (fittingly) remains undisturbed. For instance, Jacobsen’s most famous chairs have been in continuous production by the same manufacturer since they debuted in the 1950s, which is to say that they’re timeless pieces. In fact, Danish Modern design in general is often thought of as being “timeless.” While its well-conceived and well-constructed forms are certainly qualities that render it so, the driving force behind this timelessness is what the design represents. At its core, Danish Modern is based on intellect and a desire for improvement—two things that will never lose their cachet within civilization. Human rights, gender equality, socioeconomic disparity, and public infrastructure (namely education and healthcare) are all hot-button topics today, but not in Denmark. Danish Modern is timeless precisely because it was ahead of its time by about 150 years.

Works Cited

Allen, Julie K. Icons of Danish Modernity: Georg Brandes & Asta Nielsen. University of Washington Press, 2012.

Biswas-diener, Robert, Joar Vittersø, and Ed Diener. “The Danish Effect: Beginning to Explain High Well- being in Denmark.” Social Indicators Research, vol. 97, no. 2, 2010, pp. 229-246. ProQuest, https://search. proquest.com/docview/197640914?accountid=25324, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9499-5.

“Designing Danish Modern.” Treasures, Apr. 2018, pp. 32–37. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=ofs&AN=129300262& site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s8983827.

Goodhart, Maud. “Design Classic: The Peacock Chair by Hans Wegner.” FT.Com, 2015. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1752942994?accountid=25324.

Hansen, Per H. Danish Modern Furniture, 1930-2016: The Rise, Decline, and Re-Emergence of a Cultural Market Category. University Press of Southern Denmark, 2018.

Kjeldsen, Kjeld, et al. Arne Jacobsen: Absolutely Modern, edited by Michael Juul Holm et al. translated by James Manley, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2002, pp. 6–13.

Leslie, Gilbert E. “Denmark Celebrates Arne Jacobsen.” Scandinavian Review, vol. 89, no. 3, Winter, 2002, pp. 36-47. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/205167462?accountid=25324.

Linnet, Jeppe Trolle. “Money Can’t Buy Me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space.” Social Analysis, vol. 55, no. 2, Summer 2011, pp. 21–44. EBSCOhost, doi:10.3167/sa.2011.550202.

Lorenz, Trish. “How Denmark is Moving on from Modernist Past to a New Design Era.” FT.Com, 2015. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/1657250983?accountid=25324.

Munch, Anders V. 1.avm@sdu. d. “On the Outskirts: The Geography of Design and the Self-Exoticization of Danish Design.” Journal of Design History, vol. 30, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. 50–67. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/jdh/ epw049.

Mussari, Mark. Danish Modern: Between Art and Design. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Oda, Noritsugu, and Takako Murakami. Danish Chairs. Chronicle Books, 1999, pp. 7-16

Øllgaard, Gertrud. “A Super-Elliptical Moment in the Cultural Form of the Table: A Case Study of a Danish Table.” Journal of Design History, vol. 12, no. 2, 1999, pp. 143–157. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1316310.

Raoul, Rosine. “The Danish Tradition in Design.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 4, 1960, pp. 119–123. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/ stable/3257866.

“The Best Countries in the World, Ranked.” U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News & World Report, www. usnews.com/news/best-countries.

Watson-Smyth, Kate. “The Pursuit of Happiness.” FT.Com, 2012. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/1019720347?accountid=25324.

Wiking, Meik. The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living. Translated by Kurt Hansen, HarperCollins Publishers, 2017.

Biswas-diener, Robert, Joar Vittersø, and Ed Diener. “The Danish Effect: Beginning to Explain High Well- being in Denmark.” Social Indicators Research, vol. 97, no. 2, 2010, pp. 229-246. ProQuest, https://search. proquest.com/docview/197640914?accountid=25324, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9499-5.

“Designing Danish Modern.” Treasures, Apr. 2018, pp. 32–37. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=ofs&AN=129300262& site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s8983827.

Goodhart, Maud. “Design Classic: The Peacock Chair by Hans Wegner.” FT.Com, 2015. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1752942994?accountid=25324.

Hansen, Per H. Danish Modern Furniture, 1930-2016: The Rise, Decline, and Re-Emergence of a Cultural Market Category. University Press of Southern Denmark, 2018.

Kjeldsen, Kjeld, et al. Arne Jacobsen: Absolutely Modern, edited by Michael Juul Holm et al. translated by James Manley, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2002, pp. 6–13.

Leslie, Gilbert E. “Denmark Celebrates Arne Jacobsen.” Scandinavian Review, vol. 89, no. 3, Winter, 2002, pp. 36-47. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/205167462?accountid=25324.

Linnet, Jeppe Trolle. “Money Can’t Buy Me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space.” Social Analysis, vol. 55, no. 2, Summer 2011, pp. 21–44. EBSCOhost, doi:10.3167/sa.2011.550202.

Lorenz, Trish. “How Denmark is Moving on from Modernist Past to a New Design Era.” FT.Com, 2015. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/1657250983?accountid=25324.

Munch, Anders V. 1.avm@sdu. d. “On the Outskirts: The Geography of Design and the Self-Exoticization of Danish Design.” Journal of Design History, vol. 30, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. 50–67. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/jdh/ epw049.

Mussari, Mark. Danish Modern: Between Art and Design. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Oda, Noritsugu, and Takako Murakami. Danish Chairs. Chronicle Books, 1999, pp. 7-16

Øllgaard, Gertrud. “A Super-Elliptical Moment in the Cultural Form of the Table: A Case Study of a Danish Table.” Journal of Design History, vol. 12, no. 2, 1999, pp. 143–157. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1316310.

Raoul, Rosine. “The Danish Tradition in Design.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 4, 1960, pp. 119–123. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/ stable/3257866.

“The Best Countries in the World, Ranked.” U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News & World Report, www. usnews.com/news/best-countries.

Watson-Smyth, Kate. “The Pursuit of Happiness.” FT.Com, 2012. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/ docview/1019720347?accountid=25324.

Wiking, Meik. The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living. Translated by Kurt Hansen, HarperCollins Publishers, 2017.

an investigative, self-reflexive

essay on my creative practice

as it relates to social and

environmental realms

essay on my creative practice

as it relates to social and

environmental realms

Mutually Inclusive

My entire raison d’être as a designer is heavily predicated on the notion of servitude. What gives my creative practice sustenance is a never-ending desire to skillfully craft smart and innovative solutions to problems of varying complexities, because that in turn makes me feel as though I’m making a positive difference in some way. To be clear, there’s no personal gain or ego involved in this unwavering zeal for betterment. Rather, my practice is rooted in a humanitarian ethos very much in line with that of Danish Modern architects and industrial designers, particularly Arne Jacobsen—the vanguard of Danish Modernism. Jacobsen and his ilk adhered to a philosophy whereby they had a moral obligation to create things with the earnest intention of enriching the lives of others. In fact, the Capstone paper I wrote during the fall semester of my Senior year investigated Danish Modern artifacts as being allegories of a broader and uniquely Danish cultural narrative built on utopian virtues of altruism, egalitarianism, and hedonism. After developing more than just a surface-level understanding of Utopianism as a social concept and what it specifically entails however, I quickly determined that ‘utopian’ wasn’t necessarily the most appropriate descriptor of my creative practice as it pertains to social and environmental realms.

It was English humanist Thomas More who first coined the word ‘utopia’ in 1516, perhaps deliberately drawing upon the term’s etymological ambiguity. On the one hand, it may be derived from eu-topios, which means “place of happiness;” while on the other hand, it could be derivative of ou-topios, meaning “nowhere” (e.g. a place that doesn’t exist). (Huriot, 2-3) One immediately realizes that the very idea of Utopianism is a dichotomy of two conflicting extremes—a paradox that struggles between the possible/real and the ideal/imaginary. Furthermore, it becomes quite evident upon closer inspection that the latter etymology is the more plausible of the two. Utopianism, as initially conceived, is a classic case of social engineering to the most extreme degree, and therefore impossible to realize in an increasingly connected and open-minded global society. One of the hallmarks of Utopianism is the notion of boundary and enclosure. Traditional utopian cities dating back to Antiquity and the Renaissance were self-contained, isolated urban population centers cut off from the outside world by walls and/or natural barriers. (5) Inhabitants of those islands had to be consenting participants in a highly controlled society defined by a strong sense of order and uniformity across all aspects of life, from identical housing/furniture to decorum. These so-called “rules for living” even went as far as identifying an ideal “standardized man” who behaved honestly, virtuously, and altruistically against whom one was to be judged. (6) Utopianism undoubtedly has fascist undertones, and is contingent on too many quixotic axioms to render it as anything other than contrived fantasy. But while the rigid spatial and architectural organizations characteristic of utopian communities of yore are simply not viable, the underlying core values on which they were based—equality, equity, and liberty—are not only possible, but also well-intentioned and ideal. This is because Utopianism as a philosophical construct represents a critique of the status quo and the belief that a better alternative reality can be had. In that sense, this notion of Utopianism as a paradox is, quite ironically, very felicitous.

Bewildered by the contradictory nature of utopian fallacy, I was left to ponder what my creative practice truly represented to both me and my audience. After all, Utopianism represented many conceptual themes common throughout my creative practice and oeuvre—architecture, urbanism, quality of life, social responsibility, structural frameworks, etc. Naturally, the problem solver in me wanted to uncover the truth and address any incongruities one might uncover. This momentary bout of existential dubiety prompted me to investigate how I could implement a utopian value system as praxis, especially since ‘utopian’ is a label that’s oft riddled with cliché. I eventually concluded that Neo-Utopianism was a more apt ascription of my creative practice, for it provides dimensional context without compromising the aforementioned core values. Neo-Utopianism is very much a negative critique of its predecessor in that it essentially denounces it as a failed socio-environmental experiment—a case study of how something that sounds great in theory can actually be philosophically flawed and insidiously dangerous. The truth of the matter is that Utopianism, as originally conceived, demonstrates a lack of concern for social justice. (1) In fact, the truest of utopian conditions are, if anything, more likely to generate losses of equality, equity, and liberty. (1)

It’s precisely this lack of judiciousness and prudence that differentiates Neo-Utopianism from Utopianism. According to Israeli educator, social researcher, and writer Tsvi Bisk, “[t]he primary human survival tool is not instinct but the reasoning mind evaluating the human environment” and that “human society cannot conduct itself rationally [or be “vigorous and healthy”] without [clear ideas] of where it wants to go.” (Bisk, 22) My educational experience here at Otis has made me realize how much I value structure, even though I always knew that subconsciously. Freedom of self-authored projects has enabled me to devise my own methodologies in relation to the specific parameters of the conceptual dilemma I create for myself. This process includes identifying subject matter, purpose, audience, and media. At the same time, I’ve also struggled with learning how to iterate and explore multiple options, avoiding my proclivity for marrying the first thing I fall in love with (i.e. the choice of a specific typeface or the compositional layout of a book spread design), so to speak. With that being said, Bisk also argues that a multitude of realistic visions of the future are needed to hedge against uncertainties and to “avoid the totalitarian, know-it-all temptation that has doomed utopian experiments in the past,” which is to say that too much tunnel vision is actually a detriment. (22) Simply being an active participant in planning for the future isn’t sufficient, however. It also requires a hybrid Futurist-Romanticist vision—one that’s both rational and idealistic. (24) That to me speaks to the idea of having ambitions that are grand, yet tangible and malleable. Ideas are only ideas until they’re actualized, and more often than not I find that things (in general) rarely go according to plan. But one can safeguard against these unforeseen setbacks if sufficient preparation is given.

As a problem solver, I am very much attuned to the more thought-based Neo-Utopian approach. With every project I do, my methodology often involves conducting a plethora of research because I want to immerse myself within the subject matter as best I can. In doing so, I’m able to better comprehend the problem to be addressed, which in turn allows me to design solutions that are more responsive and specific to the needs of clients, audience members, and end users. In fact, I often get criticized for thinking too much instead of doing—the actualization of the idea. So while I spend lots of time doing preparative work in the form of research, I don’t allot enough time for execution, which itself is a major problem that needs a solution. But thorough investigation is, in my view, a manifestation of another key component of my creative practice—Systemic Design.

Systemic Design is all about employing a tailored approach to problem solving. Whereas Utopianism relies on far-fetched assumptions to work, Systemic Design makes no assumptions at all. Rather, the problem itself dictates the output through the use of undogmatic, flexible, generous, and innovative attitudes and approaches; there’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ mentality. (Sevaldson, 1) “If the models do not fit, or they are too cumbersome to operate, they need to be changed. Models and practices need to be adapted to real life, not vice versa,” according to Birger Sevaldson, a professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design’s Institute of Design. (1) Proaction (as opposed to reaction) is the fundamental difference between Systemic Design and Utopianism. While the latter is descriptive (e.g. knowledge of the system informs action), the former is generative and creative. (3) Systemic Design uses a much more inquisitively experimental approach whereby design deliberately provokes the system in anticipation of a reaction. By observing how it reacts, designers learn more about the system and can even create new systems. (3) This entire process of discovery is itself a system operating within a greater system; no two systems are alike. The Otis Communication Arts curriculum and its studio course pedagogy is a system that I provoked (and it certainly provoked me back), and the reaction I received came in the form of feedback from both instructors and peers. I was able to gain powerful insight into my own creative values, interests, strengths, and weaknesses.

Systemic Design also raises notions of holistic thinking, gestalt (e.g. ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts’), and gesamtkunstwerk (e.g. ‘total work of art’ that can be universally applied). Although every system has a unique structure, no system can operate with enclosure. Systemic Design must heed external parameters (e.g. the problem, the greater system at large) and react accordingly before it yields a new system. Through this dynamic exchange, the designer is tasked with “generating a single holistic response that solves, negotiates or balances some or many of the contradictory inputs in the shape of a more or less aesthetically satisfactory form,” according to Sevaldson, who acknowledges that aesthetics are an important factor because they’re an outward expression of scale relationships. (6) The interaction of exogenous and endogenous entities, and the synthesis of their parameters, is what gives Systemic Design harmony and contextual relevance. In other words, awareness of one’s constraints is reflected (but not necessarily visible) in the final output. The constraints are akin to a figure-ground perspective in that they are a simultaneous reflection of what one has and doesn’t have to work with. How well those constraints are dealt with is how effective the solution to the problem is.

The concept of gesamtkunstwerk, however, requires some reconciliation for a few reasons. First, the idea of a ‘total work of art’ has fascist undertones not unlike old-school utopian philosophy. In post-war Europe, the term fell out of usage for this very reason until a conscious effort was made to detach it from its negative connotations and associate it more with interdisciplinary notions of audience engagement, co-creation, and participation. (12) Ironically, traditional Utopianism also rests on these principles. Hence the reason why utopian cities were imagined as being situated within an urban framework, for proximity and concentration afford interaction and complementary diversity. (Huriot, 2) Another potential form of cognitive dissonance stems from the notion that gesamtkunstwerk represents static un-changeability. (Sevaldson, 13) According to Sevaldson, “[i]t is almost unthinkable to add or subtract from it or to consider that certain functions would be added at the cost of others.” (13) It should be pointed out that Sevaldson’s statement is referencing the design of a multifunctional Spanish monastery dating back to the 16th century—more or less the same historical period as when More first conceived of his Utopia. One could argue that the centuries’ worth of advancements in science and technology along with the changes in social, political, and economic power across the globe that have been realized since then are more than enough to render such a rigid interpretation of gesamtkunstwerk all but obsolete for me.

The Bauhaus restored gesamtkunstwerk back into the vernacular of the intelligentsia, emphasizing natural interdependence over planned collaboration. (14) However, the institution also didn’t fully renounce the idea of enclosure. “A resolved harmonic and holistic composition is necessarily static. It is a closed work of art because it is complete and resolved. Altering it would only result in the breakdown of the composition,” Sevaldson notes. (14) Personally, architectural preservation is one of only a few examples that could render me a strict constructionist in this regard. But as someone who hails from a culturally dynamic, ever-evolving city (Los Angeles) and considers himself to be ideologically progressive, I’m generally of the belief that nothing is ever complete or that conventions can’t be challenged.

Gesamtkunstwerk’s more interpretative end of the spectrum is such that designs that evolve over time (i.e. a cosmopolitan city such as, say, London that has a rich history yet has managed to reinvent itself in the new millennium) develops a rich patina that can only be the result of systemic processes. (15) As a creative individual, I firmly believe that any creation can never be considered complete, for there’s always something more that could be done whether that be by addition, subtraction, differentiation, or an infinite combination of those things. Even if I’m satisfied with a particular design and place it in the archives, I do so knowing that if I were to go back and make changes, I would reimagine a new system because the passage of time naturally yields new systemic contexts from a variety of internal and external forces. In my case, perhaps there was a new typeface I discovered or a particular place I visited that would compel me to make different design decisions the second time around. Furthermore, these different design decisions could reflect either the same or new intentions entirely. Of the handful of personal projects that I deem ‘finished,’ there are still aspects I would approach differently based on shifting tastes, developed skills, and acquired knowledge. Social and environmental spheres are always fluctuating, so it follows that my creative practice be responsive and flexible.